It’s hard to believe it’s already been 3 years, but I’m excited to pretty much have completed the “dreadful” pre-clinic years.

There have been many ups and downs, times I didn’t know how to react and think about certain situations. Despite this, I’m 100% satisfied with and proud of the outcome.

Sure, I gained a lot of medical knowledge. But more importantly, I adopted new perspectives because of the situations I found myself in.

Briefly:

- Grades are not as important as knowledge or experience.

- University is the last period where you have lots of time, don’t just spend it studying the whole time.

- Mindset is much more important than being (perceived) smart or intelligent.

- Be a generalist as long as possible. If you’re interested in something not 100% related to your field of study, do it regardless.

- You don’t have to be the best. Be good at a lot.

The next few paragraphs are an extension of the points above.

Grades are not as important as knowledge or experience

There are too many factors that determine what grade you get on an exam for them to be a proper representation of your knowledge. Exam type, teacher’s bias, a sleepless night, a bad day etc.

For example, I’m terrible at solving multiple-choice questions and I 100% know it and own it. But that doesn’t matter to me because I’m still confident in my knowledge and how to apply it. It’s just that when you throw multiple options at me, I’m awful at picking the correct one. On the other hand, I 100% admit that I could sometimes be better prepared for exams.

These types and similar situations are just unfortunate, but in my eyes don’t determine how good a student is (but I’m biased, of course). To me, what gives value to a student is the knowledge they possess, know how to apply it and connect it to other areas (even outside their area of study).

I adopted this perspective from Neil deGrasse Tyson on The Tim Ferriss Show (listen at 1:28:10) when he reacted to being called a “mediocre student” in an article. His grades might have been mediocre, but he was reading more than anybody else, visited observatories and took extra classes at museums in his free time. That’s far from being a mediocre student.

“If you have the bias that grades are who you are, then yes, you’re going to write a sentence in an article that he was a mediocre student.” - Neil deGrasse Tyson

University is (probably) the last period where you have lots of time

I didn’t fully comprehend this when I started medical school. My idea was that medicine is now my life and I have to devote myself 100% to it.

Then I realised that if I want to learn and experience things outside medicine, this was the time to do so.

My experience is that when we’re in primary school we’re just too young for certain things, but we can still build valuable life skills. And when we’re in high school, we’re too busy deciding what to study and then getting the grades to get there.

But this disappears in university - we’re old enough, and we’ve reached a goal, which we just have to complete. Plus, we’re given much more flexibility.

I’m not saying to not care about university (especially medical school) and the grades you’re getting. I’m saying don’t spend this time only studying and balance it out with other things you’re interested in.

Mindset is much more important than being (perceived) smart or intelligent

We understand intelligence too poorly and define it too loosely for it to be a deciding factor in life.

The deciding factor is your mindset. With a correct mindset comes the belief you can change yourself with hard work. And I sincerely believe you can achieve anything with it. Even improve your “intelligence”.

If intelligence is the mental capacity to learn and adapt to new situations, then you can improve it with hard work (gaining new experiences and knowledge). But if you don’t believe this is possible, then you will stay stagnant. That’s the difference between a growth and fixed mindset (brilliantly explained in the book Mindset by Carol Dweck).

So if I were you, I’d be much more “scared” of someone, who works his tail off than of someone, who appears to be “intelligent” or “smart”. And at the same time, I’d stop evaluating people based on their IQ score.

Be a generalist as long as possible

This is one of the most useful concepts I’ve come across in recent years. It’s fascinating that some of the most successful people in certain fields have a background in an entirely different area.

Primož Roglič started as a ski jumper and won a gold medal in cycling in Tokyo.

Anna Kiesenhofer not only won a gold medal in cycling in Tokyo but also has a PhD in mathematics.

Ester Ledecká won both super-G and parallel giant slalom in snowboarding golds in 2018 Winter Olympics.

The list goes on and on. The most visible examples are athletes, but it surely doesn’t end there. This is how Nintendo was born and how a drug against malaria was discovered.

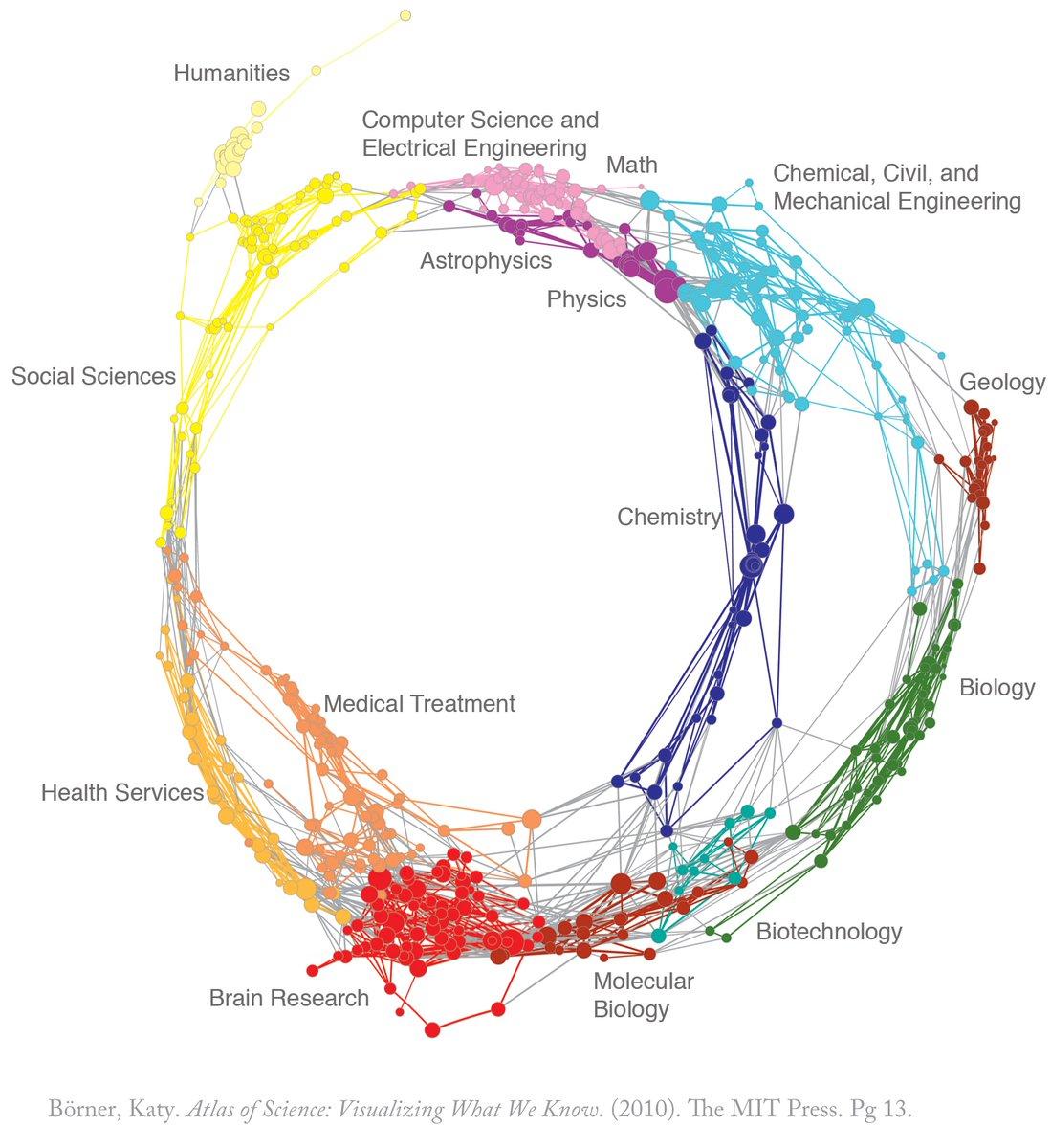

There’s something about being able to connect knowledge and experience from distant areas and create something new.

This is also our greatest strength. Computers operate in very narrow fields with strong guidelines. So if you’re worried AI will take your place, become a generalist, and it won’t come even close.

I can’t imagine not doing things apart from studying medicine. Being interested in technology and web development yielded some remarkable opportunities in life as well as in medicine. Being a former athlete allowed me to better apply studying metabolism, physiology, and pathology to real life.

If you think about it, medicine is just a combination of many “basic” fields. This also means there’s always a place for new ones, those we don’t even dare to imagine just yet.

The bottom line is if you’re interested in something that has nothing to do with your field of study, do it regardless.

Aim to fill in the empty circle in the middle on the picture below. Then you have something new.

You don’t have to be the best, be good at a lot

Being exceptional at one thing takes too much time and energy, which are finite. There’s a good chance you’ll be average at most other things.

That’s just the nature of life.

Instead of pushing yourself to be the best at one thing, aim to be good at a lot. Do more things regularly. Try to improve them step by step.

Then add to your repertoire.

I’m not the best writer, but because I’m “only” good at it, I can also be a pretty good web designer.

Being “pretty good” at multiple things helps us excel. Combining the things we’re good at makes us excellent at that combination. And it makes us more unique.

Becoming good at a lot may take a long time, but it pays off.

That’s what’s been brewing inside my mind for the past 3 years and I now put it in writing. I intend to hold on to these principles and hopefully develop new ones in the next 3 years of medical school. Let’s go!