It’s much harder to quit than to stick to something. And it’s even harder to choose what to quit and with what to stick.

I was hoping Seth Godin could help me with this dilemma in his book The Dip. This is what I learned.

Quit the wrong stuff. Stick with the right stuff. Have the guts to do one or the other.

The best in the world

There’s always demand for the best in the world. Why? Well, because when people need something, they want what’s best for them.

People don’t have a lot of time and don’t want to take a lot of risks. If you’ve been diagnosed with cancer of the navel, you’re not going to mess around by going to a lot of doctors. You’re going to head straight for the “top guy,” the person who’s ranked the best in the world. Why screw around if you get only one chance?

What makes the best in the world scarce is that their competition quit long before they achieved something. The best in the world didn’t, though.

Where does the scarcity come from? It comes from the hurdles that the markets and our society set up. It comes from the fact that most competitors quit long before they’ve created something that makes it to the top. That’s the way it’s supposed to be. The system depends on it.

But on the flip-side, the reverse is also true. If you know what and when to quit, but also know when to stick, you can develop a new product or skill that’s the best in the world. Know how to strategically quit and focus on where you can be the best. And become scarce.

Strategic quitting is the secret of successful organizations. Reactive quitting and serial quitting are the bane of those that strive (and fail) to get what they want. And most people do just that. They quit when it’s painful and stick when they can’t be bothered to quit.

That all makes sense. But we still have no idea how to identify the moment or activity you need to quit.

Supposedly, there are three curves that give you an inkling about that.

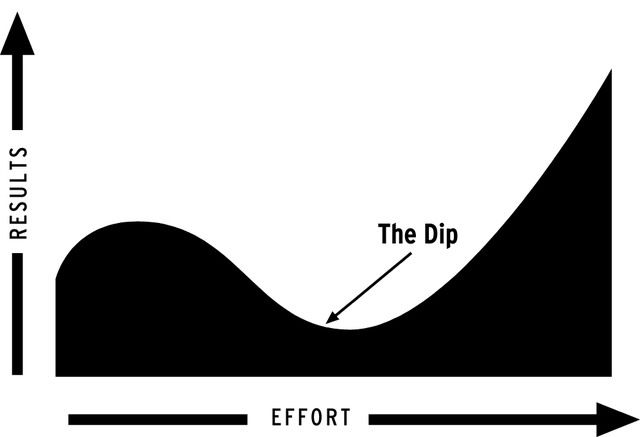

The Dip

This is the curve you have to always keep in mind. Because it’s good. Almost everything you start anew is controlled by the dip.

For example, anyone who wants to become a doctor faces the Dip. It’s all going brilliantly in grade school and high school, but then medical school comes. It’s (in my case) 6 years of intense studying until you come out on the other side and become a doctor. Some quit along the way, a lot don’t even start. But the reward for those who get through the Dip is worth it.

The Dip is the long slog between starting and mastery. A long slog that’s actually a shortcut, because it gets you where you want to go faster than any other path.

Perhaps most important of all, the dip produces scarcity. And scarcity means value.

The Dip creates scarcity; scarcity creates value.

The Cul-de-Sac

It means “dead end” in French. Godin describes it as something that doesn’t even need a chart.

It’s a situation where you work and you work and you work and nothing much changes. It doesn’t get a lot better, it doesn’t get a lot worse. It just is.

There’s not much to say apart from this is the one you have to quit.

The Cliff

This is the dangerous one.

According to Godin, you can recognise the Dip. But the Cul-de-sac and the Cliff are somewhat similar. Just that the Cliff is a lot harder to quit and has much more serious consequences.

The pain of quitting just gets bigger and bigger over time. I call this curve a Cliff—it’s a situation where you can’t quit until you fall off, and the whole thing falls apart.

The example in the book is smoking. When people smoke, they don’t feel the toll on their body for the majority of time. They actually feel good because they’re feeding their addiction. And often, they can’t quit. The problem comes in the end when they’re diagnosed with COPD or lung cancer. That’s the reality and the suffering of not quitting earlier.

If you find yourself facing either of these two curves, you need to quit. Not soon, but right now. The biggest obstacle to success in life, as far as I can tell, is our inability to quit these curves soon enough.

Are you afraid to quit?

I am. Because I’m persistent by nature. And I want to avoid feeling regret.

The risk in this approach is the waste of time (and money). At the same time, society is telling us “don’t quit” and “keep pushing”.

The brave thing to do is to tough it out and end up on the other side—getting all the benefits that come from scarcity. The mature thing is not even to bother starting (to snowboard) because you’re probably not going to make it through the Dip. And the stupid thing to do is to start, give it your best shot, waste a lot of time and money, and quit right in the middle of the Dip.

However, we have to return to the earlier thesis of being the best in the world eventually. That’s where the value is.

But quitting is what’s most difficult. You’re admitting to yourself that you’re not going to be the best in the world. It’s also a lot easier to just settle for mediocrity and stay in the Cul-de-Sac.

Quitting is difficult. Quitting requires you to acknowledge that you’re never going to be #1 in the world. At least not at this. So it’s easier just to put it off, not admit it, settle for mediocre.

It turns out it’s a lot easier to not start something rather than it is quitting it. So, the guiding principle should be this:

Simple: If you can’t make it through the Dip, don’t start. If you can embrace that simple rule, you’ll be a lot choosier about which journeys you start.

If you’re going to quit, quit before you start. Reject the system. Don’t play the game if you realize you can’t be the best in the world.

But there’s a danger to this approach. It can prevent you from trying new things and acting. That’s the other extreme you want to avoid, which is why starting, trying and quitting (if applicable) is a much better approach in my opinion.

Great highlights I didn’t use in the text

- Anyone who is going to hire you, buy from you, recommend you, vote for you, or do what you want them to do is going to wonder if you’re the best choice.

- Just about everything you learned in school about life is wrong, but the wrongest thing might very well be this: Being well rounded is the secret to success.

- In fact, the people who are the best in the world specialize at getting really good at the questions they don’t know. The people who skip the hard questions are in the majority, but they are not in demand.

- Successful people don’t just ride out the Dip. They don’t just buckle down and survive it. No, they lean into the Dip. They push harder, changing the rules as they go. Just because you know you’re in the Dip doesn’t mean you have to live happily with it. Dips don’t last quite as long when you whittle at them.

- The Cul-de-Sac (French for “dead end”) is so simple it doesn’t even need a chart. It’s a situation where you work and you work and you work and nothing much changes. It doesn’t get a lot better, it doesn’t get a lot worse. It just is.

- If you haven’t already realized it, the Dip is the secret to your success. The people who set out to make it through the Dip—the people who invest the time and the energy and the effort to power through the Dip—those are the ones who become the best in the world.

- In a competitive world, adversity is your ally. The harder it gets, the better chance you have of insulating yourself from the competition. If that adversity also causes you to quit, though, it’s all for nothing.

- And yet the real success goes to those who obsess. The focus that leads you through the Dip to the other side is rewarded by a marketplace in search of the best in the world. A woodpecker can tap twenty times on a thousand trees and get nowhere, but stay busy. Or he can tap twenty-thousand times on one tree and get dinner.

- Before you enter a new market, consider what would happen if you managed to get through the Dip and win in the market you’re already in.

- The next time you catch yourself being average when you feel like quitting, realize that you have only two good choices: Quit or be exceptional. Average is for losers.

- Yes, you should (you must) quit a product or a feature or a design—you need to do it regularly if you’re going to grow and have the resources to invest in the right businesses. But no, you mustn’t quit a market or a strategy or a niche. The businesses we think of as overnight successes weren’t. We just didn’t notice them until they were well baked.

- Don’t fall in love with a tactic and defend it forever. Instead, decide once and for all whether you’re in a market or not. And if you are, get through that Dip.

- Short-term pain has more impact on most people than long-term benefits do, which is why it’s so important for you to amplify the long-term benefits of not quitting. You need to remind yourself of life at the other end of the Dip because it’s easier to overcome the pain of yet another unsuccessful cold call if the reality of a successful sales career is more concrete.

- Persistent people are able to visualize the idea of light at the end of the tunnel when others can’t see it. At the same time, the smartest people are realistic about not imagining light when there isn’t any.

- Quitting the projects that don’t go anywhere is essential if you want to stick out the right ones. You don’t have the time or the passion or the resources to be the best in the world at both.

- “Never quit something with great long-term potential just because you can’t deal with the stress of the moment.” Now that’s good advice.

- Crichton had no stomach for cutting people open, and he decided he didn’t relish the future a medical career would bring him, regardless of how successful he might become at it. So he quit. Crichton saw that just because he had already gotten into Harvard, already earned a fellowship—already made it through the Dip—he didn’t have to spend the rest of his life doing something he didn’t enjoy in order to preserve his pride.

- If you are making a decision based on how you feel at that moment, you will probably make the wrong decision.